Author | TaxDAO

In recent years, the development and popularization of virtual assets has attracted the attention of countries around the world, and has brought new challenges and risks to financial regulation and anti-money laundering (AML)/counter-terrorism financing (CFT) work. In response, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) has extended the traditional financial sector’s “travel rule” to the virtual asset sector, requiring that when a virtual asset transaction exceeds a certain amount, the identity information of the parties to the transaction must be transmitted along with the transaction. This is the “travel rule”.

This article aims to explore the concept of the travel rule and its application in the cryptocurrency industry, analyze the progress, differences, and difficulties in implementing the travel rule in different regions, evaluate the effectiveness and limitations of the travel rule, and provide corresponding prospects.

1 Concept and Background of the Travel Rule

1.1 Overview of the Travel Rule: From Traditional Finance to Cryptocurrency

In summary, the Travel Rule is an international standard for anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing. It requires that when a financial transaction exceeds a certain amount, the identity information of the parties to the transaction must be transmitted along with the transaction (hence the term “travel”), so that regulatory authorities can track and prevent illegal activities.

- Will the SEC target cryptocurrency wallets?

- MoonLianGuaiy Harbor Treasure Hunt Activity Introduction How to integrate NFT with the real world?

- Glassnode On-Chain Data Weekly Report (2nd week of September) Liquidity tends to dry up, on-chain activity falls into silence.

The Travel Rule was initially proposed by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) in 1996 for banks and other financial institutions in the traditional financial sector, and was revised in 2001 and 2012. With the rise and development of cryptocurrencies, FATF recognized the money laundering and terrorist financing risks in the virtual asset sector, and in June 2019, expanded the Travel Rule to Virtual Asset Service Providers (VASPs), entities or individuals that provide cryptocurrency trading, transfer, custody, and other services.

1.2 How FATF Promotes the Implementation of the Travel Rule for Virtual Assets

FATF is an intergovernmental policy-making body composed of 39 member countries and regions. Its goal is to develop and promote international standards and measures for global anti-money laundering, counter-terrorism financing, and the financing of the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. FATF was established in 1989 and is headquartered in Paris. It is currently the most influential and authoritative international organization in the field of anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing.

The 40 Recommendations issued by FATF are internationally recognized standards for anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing, including legal systems, preventive measures, international cooperation, regulatory supervision, and other aspects. The “travel rule” is the 16th recommendation among the 40 Recommendations.

In June 2014, FATF issued the “Virtual Currencies: Key Definitions and Potential AML/CFT Risks”, which was the first time that FATF defined and analyzed virtual currencies, pointing out the risks of virtual currencies being used for illegal purposes, and recommending countries to take appropriate regulatory measures. This indicates that FATF recognized the impact of the development and popularization of cryptocurrencies on the global financial system and cross-border payments.

Subsequently, in June 2015, FATF issued the “Guidance: Risk-Based Approach to Virtual Currencies”. This was the first time that FATF proposed an anti-money laundering/counter-terrorism financing regulatory framework for virtual currency activities and service providers, which meant that the requirements for customer due diligence, record keeping, reporting, and supervision that originally applied to traditional financial institutions also applied to virtual currency activities and service providers. However, the definition of “virtual currency” in this framework was relatively narrow and did not effectively coordinate the regulation of virtual assets risks.

Finally, in June 2019, FATF released the “Interpretive Note and Guidance on Virtual Assets and Virtual Asset Service Providers” (hereinafter referred to as the “Guidance”), renaming virtual currency as virtual assets and including virtual assets and virtual asset service providers (VASPs) within the regulatory scope. This meant that FATF’s regulation of virtual assets was formalized and matured. The “Standards” included guidance principles for applying the travel rule to the cryptocurrency field. The travel rule requires VASPs to collect and transmit the identity information of the originator and beneficiary of cryptocurrency transfers exceeding $1,000 or equivalent amounts to prevent money laundering and terrorist financing activities. In 2021, FATF revised the “Standards” to better regulate rapidly developing virtual assets.

1.3 Overall Impact of the Travel Rule on the Cryptocurrency Industry

1.3.1 Reporting Obligations of VASPs

In the revised “Guidance” in 2021, FATF defined VASPs as “businesses that conduct one or more of the following services on behalf of or for the benefit of another person”, including:

- Exchanging or transferring virtual assets

- Safekeeping and/or administering virtual assets or instruments related to virtual assets

- Participating and providing financial services related to the issuance and/or sale of virtual assets by issuers

The document also specifies that VASPs do not include the following types of entities:

- Entities that only provide technical support or communication services

- Entities that only provide virtual asset wallet software or hardware

- Individuals or legal entities that only use virtual assets for their own purposes

VASPs that meet the above criteria have corresponding obligations under the travel rule, namely: when handling virtual asset transactions exceeding $1,000 or equivalent amounts, they must collect and transmit the identity information of the originator and beneficiary to prevent money laundering and terrorist financing activities. Specifically, VASPs should collect the following information:

- Name, account, and address of the originator (or nationality, date of birth, ID number, etc.)

- Name and account of the beneficiary

- Transaction amount and asset type

VASPs should send this information along with the transaction to the next participant, or provide it to the relevant authorities upon request. VASPs should also retain this information for at least five years and take appropriate measures based on risk assessment and regulatory requirements.

1.3.2 Overall Impact of VASP Reporting Obligations

On the one hand, the travel rule helps improve transparency and trust in the cryptocurrency industry, preventing virtual assets from being used for money laundering and terrorist financing activities, and promoting interoperability between the cryptocurrency industry and the traditional financial system.

On the other hand, the travel rule to some extent dissolves the anonymity of virtual assets. The travel rule requires VASPs to report the identities of traders and retain them for at least five years. Therefore, the cryptocurrency industry needs to balance the demands and expectations of users for data security and privacy rights.

2 Application of Virtual Asset Travel Rule in Various Countries

2.1 International Regulatory Direction of FATF’s 40 Recommendations

The FATF’s 40 recommendations are not legally binding mandatory regulations. They belong to a policy framework that countries voluntarily comply with and need to formulate and implement corresponding laws and regulatory measures based on their own legal systems and actual situations. The FATF conducts comprehensive assessments of member countries or regions’ anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing systems and measures every certain period of time to examine whether they comply with the FATF’s 40 recommendations and other relevant standards, and publishes assessment reports.

If member countries fail to meet the requirements of the FATF, they may be included in the list of high-risk or non-cooperative countries or regions. These countries or regions may face sanctions or restrictions from other countries or regions, such as increased due diligence, reduced financial transactions, asset freezes, etc.

2.2 Countries and Regions Implementing the Virtual Asset Travel Rule

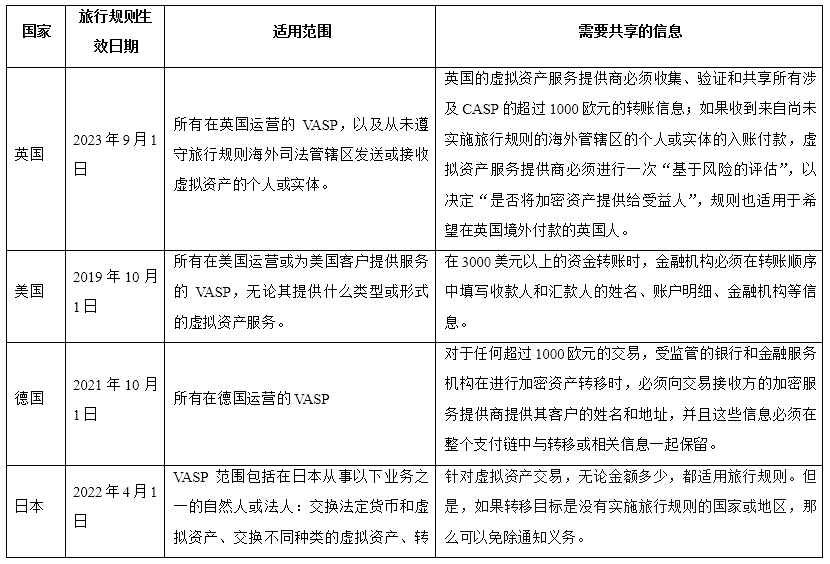

This article summarizes the countries and regions that have implemented the virtual asset travel rule as of September 3, 2023, as shown in the table below.

It is worth noting that the European Union’s Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation (MiCA) also provides corresponding guidance on the travel rule. According to MiCA, the travel rule will be extended to all cryptocurrency transactions that meet its definition, and the exemptions for minimum transaction thresholds and minimum transfer values will be removed. MiCA is expected to be implemented in February 2024, by which time the travel rules of EU member states will be more coordinated and unified.

3 Conclusion and Outlook

3.1 Effectiveness and Limitations of the Travel Rule

Travel rule has certain validity in the field of cryptocurrency, mainly reflected in its promotion of standardization and specialization in the cryptocurrency industry, and the improvement of VASP’s compliance awareness and capability. The travel rule provides VASP with a clear regulatory framework and standards, enabling VASP to conduct self-discipline management and risk control according to unified requirements. This also helps to enhance fairness in competition among VASPs and maintain market order, avoiding regulatory arbitrage or unfair competition.

However, the travel rule also has some limitations in the field of cryptocurrency, mainly manifested in the following aspects:

Firstly, it undermines the anonymity and decentralization features of cryptocurrencies, compromising users’ needs and expectations for data security and privacy rights. The travel rule requires VASPs to report traders’ identity information and retain it for at least five years, which means that personal information of cryptocurrency users may be leaked or abused, resulting in infringement of their privacy rights. At the same time, the travel rule contradicts the decentralized spirit of cryptocurrencies, subjecting cryptocurrency transactions to the regulation or intervention of centralized institutions, limiting their autonomy and freedom.

Secondly, it increases the operating costs and compliance risks of VASPs, which may lead to some VASPs exiting the market or entering the underground economy. The travel rule requires VASPs to establish and maintain a complex system for information collection, verification, transmission, and storage, which requires a significant amount of manpower, material resources, and financial resources, thereby increasing the operating costs of VASPs. At the same time, the travel rule also exposes VASPs to higher compliance risks. Failure to timely or accurately implement the travel rule may result in fines or revocation of licenses. This may make it difficult for some VASPs to withstand the pressure brought by the travel rule and lead to their exit from the market or entry into the underground economy, thereby affecting the development of the cryptocurrency industry.

Furthermore, it is difficult to adapt to the rapid changes and innovations in the field of cryptocurrency, as emerging forms such as DeFi and NFT may not fall within the scope of VASPs or be applicable to the travel rule. The cryptocurrency industry is a field full of innovation and transformation, with new technologies, products, and services constantly emerging, such as decentralized finance (DeFi), non-fungible tokens (NFTs), stablecoins, etc. These emerging forms may not fall within the scope of VASPs or be applicable to the travel rule because they may not have centralized service providers or involve traditional identity information. This poses challenges and difficulties for the implementation and supervision of the travel rule.

Lastly, it is difficult to achieve unified implementation and supervision on a global scale, as different countries or regions have differences and difficulties in implementing the travel rule. Although FATF provides a common regulatory framework and standards, countries have different progress, methods, and details in implementing the travel rule based on their own legal systems and practical situations. This brings complexity and uncertainty to cross-border transactions and creates obstacles for cooperation and communication among regulatory authorities.

3.2 Direction for improving travel rule

First, expand the scope of application of the travel rule to include more types or forms of cryptographic assets or service providers, such as DeFi, NFTs, stablecoins, etc. For example, DeFi has the advantage of providing higher efficiency, transparency, and fairness, but the disadvantage is that it is difficult to enforce the travel rule because it does not have clear service provider or customer identity information. This article believes that the built-in information sharing platform or protocol in DeFi can be used for on-chain verification, allowing DeFi traders to automatically collect, verify, transmit, and store identity information, thus achieving self-execution of the travel rule.

Second, lower the threshold for enforcement of the travel rule by eliminating exemptions for minimum transaction amounts or minimum transfer values, and apply the travel rule to all amounts of cryptocurrency asset transactions. This is to address the increasing number and segmentation of cryptocurrency transactions, as well as the regulatory challenges posed by cryptocurrency price volatility. This direction aligns with the direction indicated by MiCA.

Finally, establish unified technical standards and solutions, such as using blockchain, distributed ledgers, smart contracts, and other technologies to ensure secure transmission and storage of information. This is to address the technical barriers and security risks of information sharing among VASPs (Virtual Asset Service Providers) and improve the efficiency and convenience of information sharing, which is beneficial to the operation and management of VASPs.

References

[1] FATF. (2019). Guidance for a risk-based approach to virtual assets and virtual asset service providers.

[2] FATF. (2021). Guidance for a risk-based approach to virtual assets and virtual asset service providers (Revised).

[3] UK Government. (2021). The Money Laundering, Terrorist Financing and Transfer of Funds (Information on the LianGuaiyer) Regulations 2017.

[4] FinCEN. (2019). Application of FinCEN’s regulations to certain business models involving convertible virtual currencies.

[5] BaFin. (2020). Guidance notice on the interpretation of the term “crypto custody business” pursuant to the German Banking Act (Kreditwesengesetz – KWG) and on the authorisation requirement for crypto custody business.

[6] FSA. (2020). Amendments to the LianGuaiyment Services Act, etc. for strengthening the regulation of crypto asset-related businesses.

[7] MAS. (2020). LianGuaiyment Services Act 2019: Guidelines on licensing for LianGuaiyment service providers.

[8] FINMA. (2019). Guidance 02/2019: LianGuaiyments on the blockchain.

[9] FINTRAC. (2020). What you need to know about virtual currency transactions: Obligations under the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act and associated regulations.

[10] FIC. (2020). Guidance Note 7A: The implementation of the travel rule in terms of section 29 of the Financial Intelligence Centre Act, 2001 (Act 38 of 2001) in relation to crypto assets and crypto asset service providers.

[11] FIU Estonia. (2020). Guidelines on anti-money laundering and terrorist financing measures for providers of services related to virtual currencies or issuers of virtual currencies.

[12] European Commission. (2020). Proposal for a regulation of the European LianGuairliament and of the Council on markets in crypto-assets, and amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937.

[13] Gai Ning. (2021). Regulation of virtual currencies from the perspective of anti-money laundering: International standards and Chinese practices.

Like what you're reading? Subscribe to our top stories.

We will continue to update Gambling Chain; if you have any questions or suggestions, please contact us!