Author: Claudia Buch, Vice President of Deutsche Bundesbank; Translation: TaxDAO

Original article published on April 25, 2023

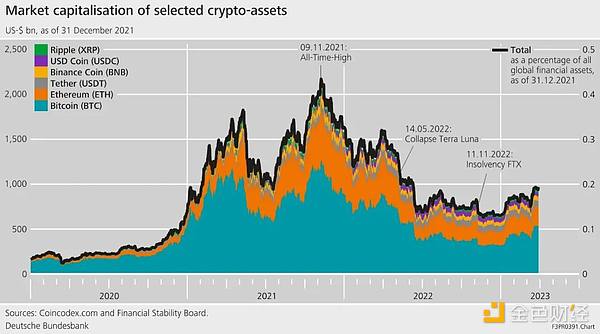

So far, the cryptocurrency market is small, with a market value of about 0.2% of global financial assets. However, if there’s one lesson we’ve learned from the past, it’s that even seemingly insignificant issues can trigger a financial crisis. Cryptocurrencies promise to provide financial services in an innovative way, much like financial securitization did in the 1990s. Securitization was considered an innovation aimed at improving risk distribution in the financial system. It started small in the 1980s and only grew to represent about half of outstanding mortgage and consumer loans by 2007. Similarly, the importance of the US mortgage market was thought to be relatively small, but it had a global impact on the financial system in 2007-2008.

Therefore, it is crucial to assess the risks to financial stability early on. In short, financial stability means ensuring the provision of services to the real economy even during periods of stress and structural change. Currently, the cryptocurrency world is not closely connected to the traditional financial system or the real economy. This might be good news. Failures and pressures in these markets may not threaten financial stability. But it could also mean the opposite: perhaps cryptocurrencies and their underlying technologies do not add much value, and high leverage in essentially unregulated markets could destabilize the core financial system?

- Pudgy Penguins clumsily entered 2000 Walmart stores.

- Interpreting the Rune protocol proposed by the founder of Ordinals Will the bone scraping therapy on Ordinals be effective?

- Binance and Mitsubishi UFJ Trust and Banking Corporation explore issuing stablecoins in Japan.

Before answering these questions and discussing the need for regulatory action, let’s first outline how we assess financial stability. In the second part, I will apply these concepts to the cryptocurrency market.

1. What is crucial for financial stability?

Different indicators are used to capture the systemic importance of financial institutions. Banks are classified as important or less important institutions based on the extent of their impact on regulation and supervision. The classification of banks uses indicators such as size, interconnectedness, common risk exposures, complexity, and substitutability. Before comparing the core financial system to the cryptocurrency system based on these indicators, it is important to emphasize that the quality of information is completely different. For the core financial system, especially banks, the quality of information is high. Banks are subject to strict regulation and required to provide relevant reports. These reporting systems have been significantly upgraded after the global financial crisis, and both banks and government authorities have paid a heavy price for it. These efforts are paying off: we now have a better understanding of the connections, risk exposures, and risk concentrations in the financial system. This information is not perfect, but it has significantly addressed the issues identified during the financial crisis, and work is still ongoing.

In the field of cryptocurrency assets, the situation is quite different. The cryptocurrency market is not yet subject to comprehensive regulation, which means that there are almost no reliable reporting systems. Some may argue that this is unnecessary. After all, transparency is one of the promises of cryptocurrency assets. All information should be public and accessible to everyone. However, public transaction data is not sufficient to monitor and assess the risks of the cryptocurrency market. For example, transactions cannot be linked to specific individuals, and many cryptocurrency transactions are conducted “off-chain”.

Unless appropriate reporting standards are adopted, we can only rely on voluntarily provided information. Such information is difficult to verify for its validity and can be manipulated. This risk is particularly high for exchanges that report their own content without regulation. Indeed, there is increasing evidence of price manipulation, especially in markets with low liquidity. Most of the data I use below about cryptocurrency assets comes from public sources. It has been validated through credibility checks, such as comparing it with data from other sources, but caution should still be exercised.

Let’s first take a look at indicators of systemic risks in the banking system.

1.1 Scale

The larger the scale of a bank, the larger its systemic footprint. In general, the banking system is dominated by a few very large participants. Therefore, specific shocks affecting these institutions may have an impact on the entire financial system. The German banking sector is no exception, with the top 1% of banks occupying 51% of the market share in terms of total assets. A large number of small banks – over 1300 savings banks or cooperative banks – collectively hold 41% of the market share.

The systemic footprint of large banks cannot be directly observed. However, statistical indicators can be used to indirectly evaluate this impact. For example, a related question is how the potential capital shortfall of a pressured large bank is related to the capital shortfall of the entire financial system. This is measured by the CoVaR method (see the graph below). Recent data for the German financial system indicates a decrease in the level of systemic risk. However, the current level is still higher than before the global financial crisis.

After the global financial crisis in 2007-2008, the G20 launched financial sector reforms to reduce the problem of “too big to fail”. Banks had become so large that their disorderly failures would cause significant disruptions to the wider financial system and economic activity.

In times of distress, banks with systemic importance often receive government bailouts. They benefit from an implicit guarantee, which becomes particularly explicit during crises. This changes the incentive mechanisms: if the ultimate risk is borne by taxpayers, financing costs may not fully reflect the risks and incentivize excessive risk-taking, balance sheet growth, and management compensation. To mitigate these risks, stricter capital requirements and regulations need to be imposed on banks with systemic importance. As an international entity overseeing the global financial system, the Financial Stability Board evaluates the effectiveness of these reforms.

1.2 Interconnectivity

The scale itself is not a sufficient indicator of the importance of a system. If the financial system is highly interconnected and banks face the same type of risks (such as interest rate risk), smaller banks may also be systemically important.

One channel for achieving interconnectedness is the interbank market. During the global financial crisis, the liquidity provided through the interbank market suddenly dried up. Due to increased uncertainty about counterparty credit risk, banks reduced their credit lines to each other. As a result, from 2008 to 2022, the ratio of interbank assets and liabilities to total bank loans in Germany decreased from 19% to 8%, while liquidity provided by central banks increased.

Although the interbank market is a channel directly affected by the financial system, common exposure to the same shock can lead to indirect effects. This risk is particularly severe at critical moments. The higher interest rates and increased risks facing growth prospects expose the vulnerability that the financial system has accumulated over the long term. Maturity conversion exposes banks to interest rate risk. Adverse shocks to the real economy can increase banks’ credit risk over a considerable range.

1.3 Complexity

A highly complex entity may be systemically important. Complexity can have different dimensions, such as the volume of derivative business, a large number of (international) subsidiaries, or operational complexity. The more complex a bank is, the higher the cost and time required to address the problems it faces. Resolving such entities requires coordination among authorities in multiple jurisdictions. A vivid example of resolving a complex entity is the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, which took 14 years to finally resolve.

1.4 Substitutability

Highly specialized financial service providers may be systemically important, even if they are small or not very complex. Payment system service providers are an example. If such institutions get into trouble or even fail, other services will also be interrupted and liquidity may dry up. The more specialized an institution is, the higher the cost of replacing its services.

1.5 Leverage

Leverage in the financial system has repeatedly triggered financial crises. High leverage makes borrowers vulnerable to adverse shocks such as rising interest rates or income reduction. This increases credit risk and leads to losses for financial institutions. Financial institutions with insufficient capital (i.e., highly “leveraged”) respond by cutting back on financial services and credit, which has a negative impact on the real economy. Therefore, the reform agenda of the past decade has focused on reducing the leverage ratio of the financial system. The capital position of banks has indeed improved compared to the past, while the leverage ratio of the private and public sectors continues to rise.

2. Are Cryptocurrencies Related to Financial Stability?

There is no simple indicator to measure “financial stability”. Instead, financial stability is formed by the complex interaction between the financial products provided, market structure, leverage and governance of financial institutions, regulation, and the motives and goals of the people providing these financial services. One important difference between traditional financial service providers (such as banks) and cryptocurrency providers is technology. Other than that, many characteristics are similar – including the potential risks to financial stability. Therefore, let’s discuss these characteristics one by one, starting with what cryptocurrencies actually are.

2.1 What are Cryptocurrencies?

Currently, there is no unified definition of cryptocurrencies internationally. According to the Financial Stability Board (FSB), cryptocurrencies are “digital assets primarily reliant on cryptography and distributed ledger or similar technology issued by private sector entities.”

The traditional financial system uses traditional IT infrastructure. Securities transactions and holdings are recorded in a central database (“ledger”) by a central securities depository. In contrast, cryptocurrencies are issued and recorded on a shared distributed digital ledger (“blockchain”). The most popular blockchain for cryptocurrencies is public and permissionless. “Public” means that all transactions are visible to everyone, but in pseudonymous form: participants in the network interact with each other using identifiers, but the actual identities of the participants are often unknown. “Permissionless” means that anyone (a “miner” or “validator”) can use computerized processes (“consensus mechanisms”) to validate transactions and meet the technical requirements to add new information. Depending on the underlying consensus mechanism, mining and validating certain cryptocurrencies require a significant amount of computational power, making the process highly energy-consuming. For example, the energy consumption of cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin is comparable to that of a medium-sized country like Spain. Despite these technological differences, cryptocurrencies share common features with traditional financial systems: trading on markets and exchanges, providing payment services, lending, or using collateral in financial transactions.

There are two types of cryptocurrencies that are relevant:

The first type of cryptocurrency is “native” tokens. These assets have no physical or financial asset backing, hence they are labeled as “unsecured” cryptocurrencies. This sets them apart from traditional financial instruments or currency. Unsecured cryptocurrencies have no intrinsic value and no cash flow support, and their prices are entirely driven by sentiment. The two most well-known native tokens are Bitcoin and Ether. Native tokens are an integral part of permissionless blockchains as they reward miners or validators for solving transactions by adding new blocks to the chain.

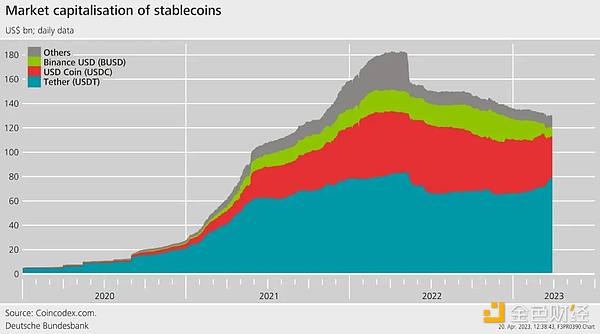

The second type of cryptocurrency is stablecoins. These currencies are mostly pegged to central bank currencies such as the US dollar. The development of stablecoins is primarily aimed at overcoming the inefficiencies and reducing costs of traditional payment systems. Despite being called “stable,” the market valuations of stablecoins actually fluctuate quite a bit. Additionally, some stablecoins have not undergone comprehensive audits, and they only disclose their reserves on a voluntary basis. Therefore, the existence and composition of reserves are not always verifiable.

2.2 Scale and Market Structure

In 2021, the total market value of all cryptocurrencies traded on exchanges reached a historical high of approximately $30 trillion (see the figure below). In the first half of 2022, the prices of cryptocurrencies plummeted. In addition to changes in the macroeconomic environment, the price decline also reflects the widespread use of leverage. Many cryptocurrency intermediaries became insolvent, and the market value dropped to $1 trillion in early 2023, accounting for only 0.2% of the total global financial assets.

Furthermore, the market is highly concentrated. The top six tokens account for more than 70% of the market value. As for the issuers of stablecoins, 90% of the market value is concentrated in the three largest entities (see the figure below). A significant portion of cryptocurrency trading occurs on a few platforms. Centralized cryptocurrency service providers and cryptocurrency groups offer a variety of services, such as brokerage, trading, settlement, custody, clearing, and settlement. However, this concentration of activity may lead to conflicts of interest and excessive risk-taking.

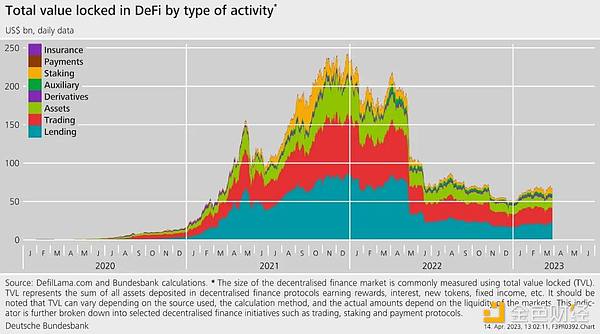

Some cryptocurrency activities have shifted towards decentralized finance (DeFi). In this model, financial intermediaries are replaced by autonomous (and automatically executed) open-source software protocols deployed on public blockchains. Unlike centralized cryptocurrency exchanges where most transactions are initially settled off-chain, all transactions in decentralized finance are executed on the blockchain (“on-chain”). Modifications to the software code should not be decided by central institutions but by the “community” and “governance tokens” representing voting rights.

While it sounds like a decentralized system, in reality, it is often highly centralized. The monitoring and governance of DeFi protocols are often held by a few founders or developers who gradually transfer these rights to a broader community. Therefore, only a few projects operate in a truly decentralized manner.

A key indicator for assessing the scale of DeFi is the Total Value Locked (TVL), which reflects the total value of cryptocurrencies transferred to the underlying software code of DeFi protocols. These codes are called “smart contracts.” These protocols can replicate a wide range of financial services, but currently, the most important ones are lending and trading of cryptocurrencies. After a very strong growth in 2021, the size of the global DeFi market dropped significantly in 2022, consistent with the overall development of the cryptocurrency market (see the figure below).

In today’s most important blockchains, validators join a group. The resulting high concentration at the validator level may have a negative impact on the security and transparency of the blockchain.

2.3 Interconnectivity

The cryptocurrency ecosystem is highly interconnected, as evidenced by the recent bankruptcies of many cryptocurrency entities. Therefore, pro-cyclical sell-offs can affect the overall volatility of the cryptocurrency market.

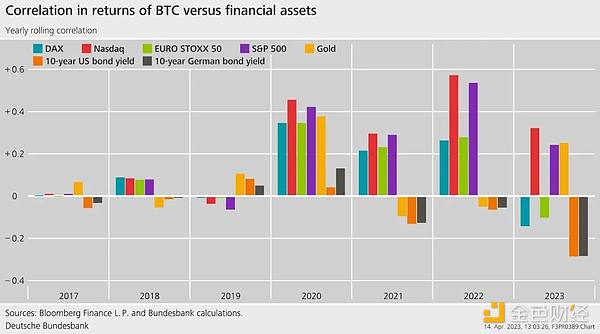

The common risk exposures in the crypto asset system are largely analogous to the risk exposures in the traditional financial system. Especially since 2020, the prices of crypto assets have been responsive to macroeconomic fundamentals such as monetary policy shocks. In recent periods of increased macro-financial risk, the prices of crypto assets have sharply declined, aligning with traditional asset classes like stocks (see the chart below).

In addition, the crypto asset system faces higher settlement and operational risks in a few blockchains. For example, nearly two-thirds of DeFi activity is based on the Ethereum blockchain as a settlement layer. The crypto asset system also faces liquidity risk. Only a few stablecoins are crucial for the liquidity of crypto asset trading, and they are widely used as collateral for loans or margin trading. The liquidity of the crypto asset system specifically depends on several stablecoins pegged to the US dollar. They are primarily supported by investing in money market instruments, making the system vulnerable to shocks in the money market.

Currently, the correlation between the crypto asset system and the financial system is not high. As long as crypto asset entities themselves do not have the necessary licenses, they rely on banks to serve as bridges between central bank currencies and the crypto asset world to obtain funding. However, as of the end of June 2022, only a few active international banks reported exposure to crypto assets, accounting for only 0.013% of total exposures.

2.4 Complexity

Crypto asset providers can be highly complex. Crypto asset groups are similar to financial groups with complex risk profiles. They not only operate as pure exchanges but also provide many different services within a single entity, including custody and derivatives trading.

In the traditional financial system, these activities are separated or subject to prudent requirements to prevent conflicts of interest. For example, in the case of FTX, there is no similar separation or sufficient governance structure. Crypto asset groups provide financial functions in multiple jurisdictions and operate through a global network of branches. Some companies are headquartered in unregulated offshore areas or have no known headquarters at all. Furthermore, in a decentralized system without proper governance structures, it is difficult to enforce accountability on specific individuals. This hinders efforts to effectively regulate through domestic regulatory authorities in the absence of international agreements without regulation and oversight.

2.5 Substitutability

Some blockchains and assets in the crypto system are difficult to replace in the short term. Currently, the crypto system is largely self-referential, with crypto assets being rarely used outside the crypto system. This limits the negative impact on the broader financial system or the real economy. However, the situation is different in some developing countries. For example, El Salvador has announced Bitcoin as legal tender. But even in countries actively promoting the use of crypto assets as a means of payment, there still seem to be restrictions on crypto assets.

2.6 Leverage

Whether in traditional finance or the cryptocurrency market, high leverage is a major risk to financial stability. High leverage amplifies the boom and bust cycles within the cryptocurrency system and can become a channel for transmitting shocks to the traditional financial system.

Leverage is a particular concern in the cryptocurrency system because collateral is typically composed of unsecured cryptocurrencies that have no intrinsic value and are highly volatile. The borrowed funds are often used as collateral for other loans, creating a “collateral chain”. In the event of a sudden price drop, the assets used as collateral are automatically liquidated, amplifying the price decline and potentially triggering a chain reaction.

Cryptocurrency exchanges allow for leveraged margin trading and often lend out cryptocurrencies to users in the form of collateral. In these margin trades, users can borrow cryptocurrencies worth up to 20 times the value of the collateral. Some exchanges also offer leverage derivatives with leverage ratios of up to 100 times.

During recent market turmoil, leverage has indeed been a key transmission pathway. The collapse of stablecoin TerraUSD in May 2022 resulted in significant losses for high-leverage cryptocurrency hedge funds. As a result, they were unable to meet the requirements for additional margin, leading to the bankruptcy of cryptocurrency lending platforms. Additionally, FTX’s bankruptcy was caused by lending customer funds to affiliated entities engaged in margin trading activities.

Like what you're reading? Subscribe to our top stories.

We will continue to update Gambling Chain; if you have any questions or suggestions, please contact us!